The Art of Living Together: How Culture Shapes Community Living

Written By Francesca LubegaIf you were to search for the definition of community living, you would find an array of definitions that depend on the context and who is writing-- government, individuals, or community organizations. For this article, I’ll define community living as existing as part of a larger group where interdependence, a shared lifestyle, and collective responsibility are integral.

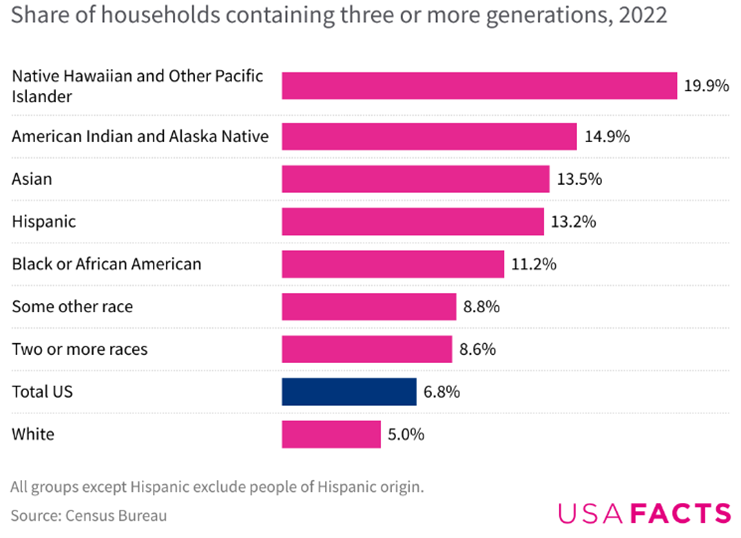

Community living varies widely across regions and cultures. Among some minority groups, particularly non-white communities, multigenerational households remain common—reflecting deep-rooted cultural traditions of care and shared living. In contrast, for broader American society, there has been a shift from interdependence to independence. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the number of single person households has more than tripled between 1940 to 2020, and non-white populations make up majority of multigenerational households.

Share of households containing three or more generations, Source: Census

Community living doesn’t always constitute being under the same roof as other people. It can also mean a sense of belonging and a collective responsibility to one another. In recent years this has been created through intentional communities, communes, and community led initiatives.

In this article, we’ll explore similarities and differences between community living across cultures and the role of architecture in sustaining community living. To do this we must first understand the historical and cultural foundations of community life.

Table of Contents:

Historical and Cultural Foundations

Western Shift Away from Community Living

Cultural Approaches to Community Living

Historical and Cultural Foundations

Community living is one of the oldest social structures in human history. People have always lived in tight knit groups out of necessity—for survival, safety, food gathering, and shared knowledge. Community living and norms vary across regions but at their core they all embody cooperation, reciprocity and kinship.

In many indigenous North American and African societies community living is centered around extended families and clans. Clans determined social status, inheritance rights, and access to resources within the community. In the past, clans aligned themselves with other clans or tribes to facilitate trade and cooperation. Land was typically owned collectively, and child caring, farming and decision-making were a shared responsibility. North American tribes like Iroquois built longhouses where multiple families of the same clan lived together.

Indigenous communities regardless of geography tend to root their living systems in symbiosis with the land, with an emphasis on stewarding the land together. This can be seen in tribes like the Yanomami (Amazon), Ba’Aka (Congo Basin), and with nomadic groups like the Tuareg. In all these cases, land wasn’t owned—it belonged to all in a reciprocal relationship.

In Asia, multiple generations lived together under one roof with shared agricultural tasks and collective elder care. While in Medieval Europe, villages shared fields, communal ovens, and cooperative grazing lands.

Western Shift Away from Community Living

After the industrial revolution, the western world began to shift away from community structures— urbanization, privatized property, and the nuclear family model changed everything. Capitalist economies championed ownership, competition, and self-sufficiency; Community housing became associated with poverty, and independence became a mark of success.

The post WWII suburban boom in the United States exemplified this shift through new zoning laws, car culture and single-family homes with fragmented community life which replaced shared spaces with fenced-in yards. Despite greater connectivity through technology, modern western life has proven to be isolating — with work-from-home models, virtual relationships, and social media weakening community bonds.

In recent years there has been a resurging interest in community living in the form of co-housing, eco-villages, and intentional communities. These modern adaptations reflect a yearning to return to collective action, connection and sustainability—values that indigenous and ancestral societies held dear.

Community living has evolved differently across the board, and next we’ll investigate how different cultures approach community living today, the common themes and differences, and what we can take away.

Cultural Approaches to Community Living

In North America, intentional communities often reflect a countercultural movement since particularly in the U.S. there has been a historic emphasis on private property and market-driven housing which shaped urban sprawl. Therefore, when we see a rise in tiny home villages, co-living spaces and co-ops, they challenge the norms by promoting shared resources, affordability, and community care. One of the longest standing ones is Twin Oaks in Virginia which fosters economic interdependence and rejects notions of total self-sufficiency.

In many parts of Asia, the family unit remains central to community life. Multigenerational households are the norm in countries like India, China, Japan, and the Philippines, where grandparents, parents, and children live under one roof or in close proximity. There is a shared caregiving where grandparents typically care for children while parents work, and there is a moral and social obligation to care for elders.

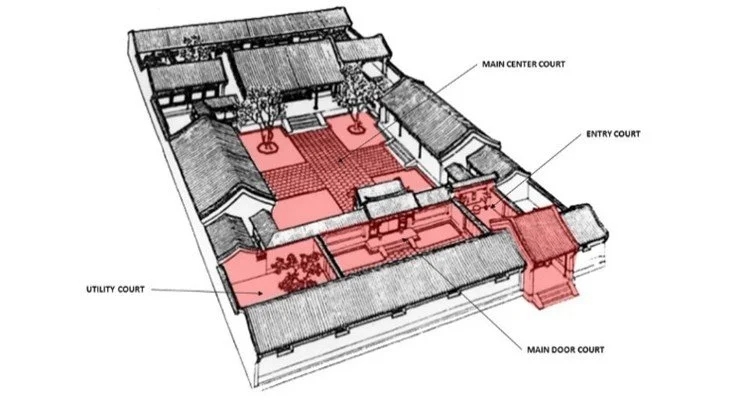

In rural China, traditional SiHeYuan courtyard homes were designed to house multiple generations, promoting a shared lifestyle. Technically SiHeYuan is a compound with many individual houses, its modules are capable of being duplicated and expanded when desired, and the designs of the houses were based on principles of FengShui—creating harmony with individuals and their surroundings.

SiHeYuan Courtyard via Davidyek

SiHeYuan Courtyard via Davidyek

Similarities and Differences

While community living looks slightly different across the globe, shared responsibility, democratic decision-making, and sustainability are at the core of these. All models emphasize collective contribution, valuing everyone’s voice, and a care for resource management and environmental consciousness.

Culture really shapes the biggest differences. Asian and African models are often familial or kin-based, while European and North American models are ideologically driven—typically based on shared values rather than blood ties. Indigenous communities may include rituals, and ceremonies as central to daily life, while modern models tend to be more secular. Lastly, decision -making looks different within these communities where more traditional approaches may still be top-down through elders, or patriarchs, and more modern ones may have more horizontal structures and have other forms of consensus.

The Future of Community Living

Co-Housing Models could deliver solutions to growing urban loneliness, childcare shortages and elder care challenges in cities. Intentional communities support intergenerational interaction and shared responsibilities—neighbors may co-parent, share elder support, and create daily moments of connection that reduce isolation. But for these models to truly thrive, we must also reimagine the spaces between our homes.

Major American cities can benefit from reviving “Third Spaces” by creating developments intended to create more shared spaces —cafés, libraries, community gardens. The term originally coined by Ray Oldenburg describes accessible, neutral, free grounds that allow a sense of community. Third Spaces are embedded in proximity with no economic or social barriers, allowing all members of the community to co-exist.

Housing developments could borrow from courtyard homes and village layouts that promote interaction, veering away from the isolation of the single-family home. Most importantly, we must foster diverse communities that are adaptable and inclusive. These spaces must be built with inclusivity, affordability, and adaptability at their core—ensuring they serve not just the affluent, young, or old, but all members of a diverse city.

Conclusion

In a time of increasing social fragmentation, the resurgence of community living is more than just an alternative housing model—it offers a path towards resilience. Across history and cultures, community living is not just shelter, but offers support systems, shared responsibility, and a sense of belonging. With the rising cost of living and widespread fatigue, community living helps us confront challenges that no individual or household can tackle alone.